Beer Yeast Database: The Complete Guide

Beer would just be sugar water without yeast. Yeast chew up sugar and turn it into alcohol and a host of other by products.

Read More: Yeast Substitution Chart

For the most part, home brewers rely on two types of beer yeasts to make our favorite concoction. Ale and Lager yeasts are the two most common. While work essentially the same, there are a few minor differences between the two that make each one their own species.

Ale Yeasts (Top Fermenting)

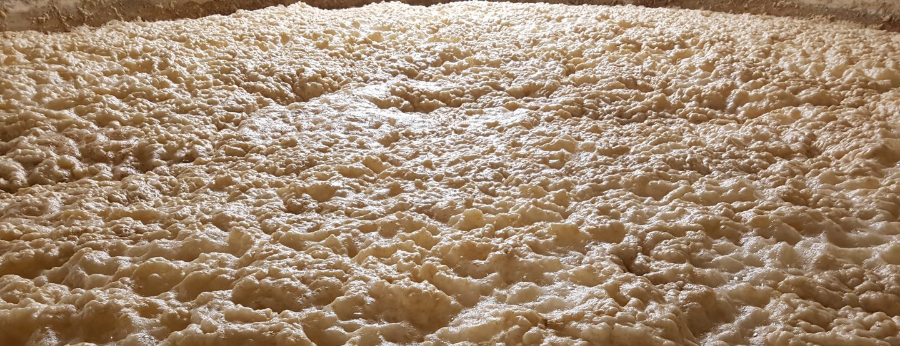

Ale yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) rise to the top of the fermenter as they propagate and work at chewing up sugars. This is what is meant by “top fermenting”. These yeasts typically work between an ideal temperature range of 60-73 °F (18-22 °C), although some individual strains can go lower or higher than that. This temperature range is perfect for home brewers as it is fairly easy to maintain regardless of circumstances.

Some ale strains produce fruity esters while they ferment while others produce a remarkably clean profile with very little character added. Flocculation and alcohol tolerance is across the board from low to high, so no matter the beer you want to brew, an ale strain will likely work just fine.

Ale yeasts are used to of course brew ales, but also stouts, porters, wheat beers, kölsch and blondes.

Popular Ale Yeast Strains

- Conan (The Alchemist)

- Chico (Sierra Nevada)

- Boddington (London Ale III)

- PacMan (Rogue Ale)

- Denny’s Favorite

- Hefeweizen

Lager Yeasts (Bottom Fermenting)

Working at colder temperatures than Ale strains, Lager yeast (Saccharomyces pastorianus) also ferment much slower. Most lager yeast strains ferment at the bottom of the fermenter, and work within the temperature range of 44 to 60°F (7-15°C).

Lager yeasts are commonly average at eating all the available sugars and are highly flocculant, meaning they drop out of the beer so it becomes clear.

The colder temperatures lager work at inhibit the production of chemical products or off-flavors that can be more pronounced in ales. This is why lagers have a so-called “cleaner” taste than ales with a more pronounced malt backbone. You would use lager yeasts to brew… wait for it… lagers(!), but also pilsners, bocks, Märzens, and dortmunders.

Others

There are a handful of yeasts that are not Ale or Lager, and each one has their own special flavor and profile.

Brettanomyces bruxellensis are used to create “brett” style or sour beers and have extremely high attenuation rates. Brett yeast strains are commonly pitched in the secondary fermentation stage.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae variety diastaticus strains (sometimes identified with a STA1 label) are also known to be extremely high attenuators due to the “contamination” of the STA1 gene. Many of these strains are considered good for making Saisons.

Bacteria-positive yeasts are strains that are known to have a bacterial strain housed within them. Many of these “blends” are used for creating sour beers due to the sourness added by the bacteria. There are some yeast packets available that are 100% bacteria, which add flavor but no alcohol.

Bacteria are used to sour beers just like the Brett strain of yeast. They however do not create any alcohol and are usually used to kettle sour a beer before a yeast strain is added to finish the fermentation.

Yeast Characteristics

Each yeast strain has its own characteristics that make them unique and suitable for different bear styles. There are five major qualities that pertain to each particular yeast strain. Most of these qualities are expressed in ranges because the surrounding elements and ingredients of the beer have just as much to do with how these yeasts perform.

Exclusive Tool: Yeast Comparison Wizard

Attenuation

Attenuation refers to the percentage of sugars in the wort that end up being converted into alcohol. Attenuation is often referred to in either percentages or with “low”, “medium” or “high” terms.

- High Attenuation: 78% and higher

- Medium Attenuation: 73% to 77%

- Low Attenuation: 72% and lower

Alcohol Tolerance

Alcohol tolerance refers to how much alcohol the yeast can sustain before becoming inactive. As the alcohol content (ABV) increases, the yeasts begin to “go to sleep” and stop fermenting. The more alcohol a yeast strain can handle, the higher the ABV will be in the finished beer.

- Low: 5% and lower

- Medium-Low: 4-8%

- Medium: 5-10%

- Medium-High: 8-12%

- High: 10-15%

- Very High: 15% and higher

Flocculation

Flocculation refers to the tendency of yeast to form clumps called “flocs” that drop as fermentation finishes. Yeast flocculation can be classified as high, medium, or low. Highly flocculating yeasts sink to the bottom of the fermenter more quickly and produce a clearer beer.

Optimal Temperature Ranges

As we touched on above, ale and lager strains ferment at vastly different temperatures. What doesn’t change between the two kinds is that if the temperature is too high or too low, bad things can happen. If the temperature is too low, fermentation could be slow to start or never finish. If it’s too warm, you risk producing off-flavors that’ll force you to dump the beer down the drain.

Flavor Profile

Defining a yeast strain’s flavor profile is difficult, and takes some guess work. When a manufacturer says that their strain imparts a “fruitiness”, they don’t mean that it actually adds fruit. They mean that the esters produced by the yeast kind of taste like fruits.

Yeasts can do so much to transform the final flavor of your beer. They can accentuate your beer’s maltiness or hoppiness profiles, or add fruity, sweet, or dry finishes.

Beer Yeast Database

Beer Maverick has compiled the largest and most complete yeast database anywhere online. We’ve spent months getting the attenuation, optimal temps, descriptions and more for over 400 beer yeasts.