The Rise and (Eventual) Fall of the CTZ Hop

CTZ is an acronym for Columbus, Tomahawk, and Zeus, three trade names owned by various private corporations for what is essentially the same variety of hop.

CTZ ranks among the most widely grown hops in the United States (second overall to Citra) and is planted in all major American growing regions.

The line of hops collectively known as CTZ are considered a “super alpha” variety. Super‐alpha cultivars have an average percentage of alpha acids greater than 15%. CTZ hops have aroma descriptors that include black pepper, licorice, curry and subtle citrus.

Mystery Parents

The hops collectively known as CTZ were developed by Chuck Zimmermann, formerly a USDA hop research scientist stationed in Prosser, Washington. When Zimmermann resigned his USDA position in 1979, he moved a large part of what he considered the “most valuable breeding material” to his personal location as he started work as a private hop breeder.

While not exactly “allowed”, Zimmerman’s private use of a USDA hop germplasm was controversial. There was no proof that Zimmerman ever sought or received permission to use this breeding material privately.

While at Hop Union, Charles Zimmerman selected a plant from test plots that would eventually become Columbus. However, he would leave Hop Union for a competitor before that plant became commercialized.

Sadly, the world may never know the exact lineage of the Columbus hop. Charles Zimmerman declined to tell anyone of the variety’s breeding specifics. When he died in 2009, he took that knowledge with him to the grave.

Regardless, there is a lot of speculation as to what this hop’s parents may actually be. It is widely assumed that Brewer’s Gold is a large part of its genetic material, along with a couple undisclosed American varieties.

Competing Companies

While patenting hop varieties is common practice now, it was not always the case.

Today, almost every popular hop that makes its way onto the market is owned by a specific breeder. Citra (HBC), Mosaic (HBC), Galaxy (HPA), Amarillo (Virgil Gamache Farms), Simcoe (Yakima Valley Ranches)… the list can go on forever. However, back in the early 1980s, patenting a new hop variety was a novel idea. This process started once the law that restricted patenting a plant variety was changed.

One of the first hops that jumped on this new-found ability was Columbus.

In 1993, Zimmerman’s successor at Hop Union (Dr. Greg Lewis), led the charge to apply for a patent for the hop now known as Columbus. It was eventually approved and assigned to a new joint venture named HUSA-CEZ, LLC (Hopunion USA-Charles E. Zimmerman).

Unfortunately, at the same time, Yakima Chief Hops began a filing for a patent on the same plant they decided to name ‘Tomahawk’. An agreement was ultimately reached that allowed Yakima Chief Hops to obtain a trademark on the Tomahawk name, while the plant was still under patent by Hop Union.

A few years later, S.S. Steiner applied to patent their new super-alpha hop called Zeus, which it does not appear that Hopsteiner was able to secure. While Zeus was found to be slightly different genetically than Columbus or Tomahawk, it was close enough to warrant being lumped in together under the CTZ moniker.

In fact, Zeus and Columbus hop rhizomes are available so that home brewers can grow their own CTZ hops.

Cracks in the CTZ Reign

CTZ hops are starting to see their popularity fade a bit over the last couple years.

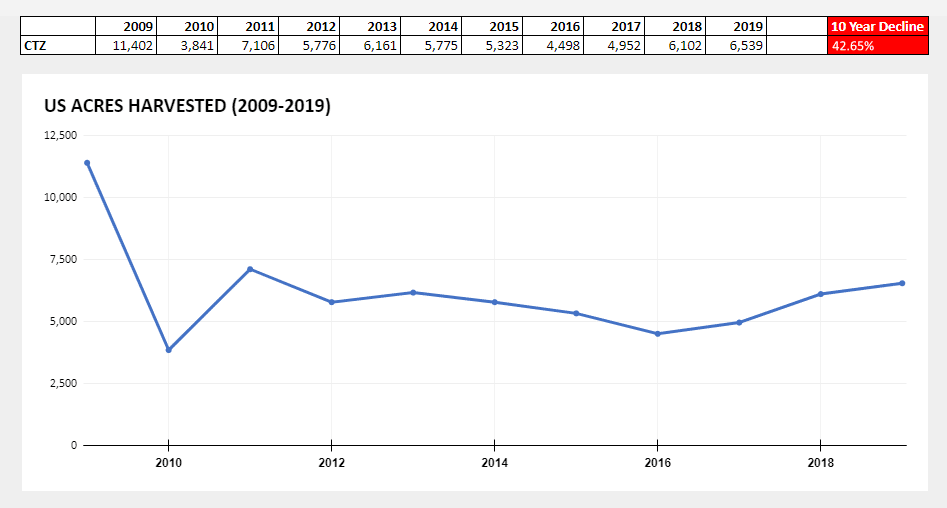

US hop producers have dropped their acreage dedicated to CTZ hops by over 42% percent in the last 10 years. While there has been a modest increase over the last four years, it is still well below its 2009 highs. CTZ saw its production increase as the sales of craft beer skyrocket, but it lags behind in the notoriety and “it-factors” that the hordes of new hops being released out of Australia and New Zealand have.

One reason for CTZ’s decline from the early 2000s is due to its very poor storage characteristics and susceptibility to powdery mildew, aphids and mites. These problems can ruin a hop production facility that is not prepared.

CTZ hops have average yields that are a still respectable 2,000 to 2,500 pounds per acre. However, in storage, it has little stability and must be processed into pellets or extracts almost immediately. Unfortunately freezing alone is not enough to preserve it.

Columbus hops have a Hop Storage Index (HSI) of 0.40 to 0.50, meaning that it retains only on average 45% of its alpha and beta acids after 6 months storage at room temperature (68°F or 20°C). An HSI this low is considered especially poor.

As it turns out, CTZ may continue to be a popular hop for brewers nationwide, but there is enough evidence that a decline is inevitable. Hop producers simply can’t afford to continue to dedicate so much of their fields to a hop that is waning in popularity and has the issues we noted above.