Why are Hops so Expensive?

Hops are expensive. They range anywhere from $2.50 per ounce to over $5 for coveted varieties such as Galaxy and Sabro. Certain beer styles – such as New England IPAs – regularly require up to 2 ounces of hop pellets per gallon to make. This massive amount of hops make it one of the most expensive ingredients when brewing beer, commonly taking up over fifty percent of a hop-heavy recipe’s budget.

When I first started brewing my own beer, I would commonly try to cut back on the amount of hops I’d use. If a recipe called for 10 ounces, I would try to make 5, 6 or 7 ounces work. It never came out with bad beer, but the decreased amount of hops definitely had a noticeable impact.

I’ve always wondered what makes them so dang expensive. Well, my curiosity finally got the best of me this week. I went and did the research to find out why. As it turns out, the companies responsible for bringing us hops are sometimes just scraping by.

Facility Costs

Starting a hopyard is really expensive.

In 2016, USA Hops working with the University of Vermont estimated that a new five-acre facility would cost over $187,000 in capital just for the initial infrastructure, equipment and labor. That does not appear to include land purchases either.

However, hopyards don’t start making money immediately after being setup. The same research shows that the same new 5-acre hopyard would lose over $159,000 dollars throughout the first five years of its existence.

Future Investments

Hopyards don’t stop spending after the initial setup either.

Between 2012 and 2019, Perrault Farms, Inc. in Washington has averaged approximately $5 million per year in capital expenses in land and facilities, compared to an average of $150,000 per year in the previous decade.

These costs aren’t limited to a few farms in the US. Hops Australia (HPA) is also in the midst of a $35 million expansion with the goal of increasing their total hops production to 2,400 metric tonnes by 2024.

Stagnant/Falling Revenues

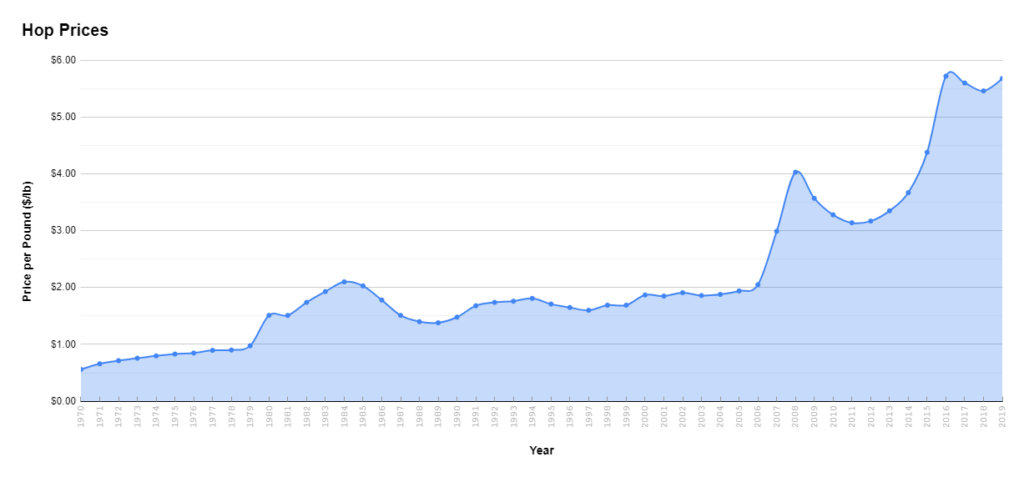

While we all complain that hops are expensive, they are actually slightly cheaper now than in 2016… by 4 cents. While only 4 cents, these amounts are amplified over the millions of pounds of hops harvested each year. However, the price of hops has generally increased over the last few decades, so the cost is trending upwards for producers.

Hop prices started to gradually fall in the last few years for a number of reasons, but the most prominent is a simple case of supply-and-demand. While craft beer drinking continues to soar, overall it’s a different story.

In the five years prior to 2018, IWSR Drinks Market Analysis shows that beer volume consumed in the US declined by 2.4%. The trend does not appear to be reversing itself either. Sales of domestic beer slipped 4.6% between October 2018 and October 2019, according to Nielsen.

Field Costs

Upkeep on hop yards can be a significant cost as well.

A major risk in the hop growing business is the constant threat of pest outbreaks or mildew spikes. Downy mildew, beetles and aphids are only some of the problems that hop farmers have to be on the lookout for.

To prevent an inadvertent spread of a catastrophe across all their fields, farms have resorted to extreme measures. They bleach tools, use disposable items, and thoroughly clean equipment before moving to a new field. This is because once a plant is virally infected, it is infected for life.

A risk I wasn’t aware of until my research was the need to prevent seeds in hops. Yakima Chief Ranches has a team of interns constantly scanning their fields for rouge male and off-type plants.

The male plants produce pollen that can result in fertilized female flowers, which will then contain seeds. The presence of seeded cones can be costly and undesirable for both growers and brewers alike. Seedy cones will impact the weight, the quality of lupulin, and the overall quality of the hops. Brewers using seeded hop cones can inadvertently add fatty acids to their beer that may cause stability issues and production of off-flavors down the road.

Natural Disasters

2020 provided quite the example of how a natural disaster could wreak havoc on the hop industry. In September 2020 wildfires swept through the Pacific Northwest, forcing untold field damage and extra work.

Yakima Chief Hops had to invest in new tests to see if the wildfire smoke impacted the aromas of their 2020 crop (it didn’t). BC Hops (an independent farm in Oregon) had to harvest their crop in ‘Armageddon’-style conditions with added staff to get it done in time. Coleman Agriculture is beginning to bring many of their baling facilities inside and away from the open air because of the regular wildfires.

All these extra precautions and work cost money – money that will not be able to be recouped since it’s just a cost of doing business now.

Breeding New Hops

Similar to the way pharmaceutical companies spend a huge part of their budget on creating new medicines, hop companies do the same with hops. New and exciting hops are the lifeblood of the hop industry.

Now breeds of hops take years to come to market. In fact, there were 17 years between when Citra was initially bred to when it finally was available for commercial use. It took another 11 years before Citra would top Cascade as the most-grown hop in the United States.

However, there is no example more jarring than what’s been happening in New Zealand. Nelson Sauvin is by far the top hop in the southern Pacific island country, accounting for over 85% of their production volume in 2019. Unfortunately, this cash-cow crop that so many NZ farmers rely on, may be nearing an end. The 20-year exclusive plant variety rights on the Nelson Sauvin hop are set to expire in late 2020. They needed a replacement to make up the potential in lost sales as more farmers begin to also sell the uber-popular hop.

NZ Hops knew they needed to find a new exclusive hop to keep the money flowing.

A 2016 cultivar named HORT 4337 was found and was initially nicknamed ‘WOW’ by selectors for its sensational aroma. In the years that followed, there were extensive viability tests and brewing trials done on this new hop. These testing years take boatloads of capital with only the faint hope of one day being able to recouping it. In 2020, HORT 4337 was renamed Nectaron, and released to the world. It has the same intense tropical fruit and citrus aroma characters that were evident during selection.

Unfortunately, not all new hop breeds are success stories like Citra and Nectaron.