What are Experimental Hops?

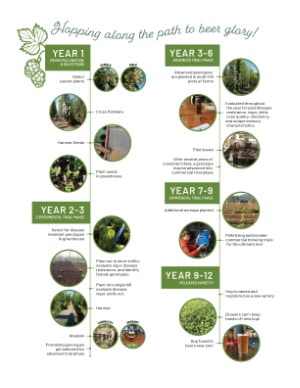

Experimental hops are hops that are still working their way through the viability phase of their breeding program. We as brewers are taking advantage of the end result of what is typically a multi-year process.

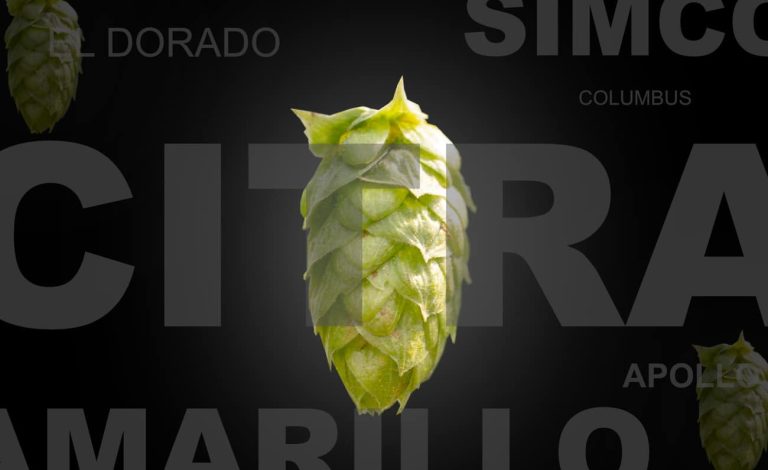

Before Citra was Citra, it was an experimental variety named HBC 384. Before Amarillo was Amarillo, it was VGXP01. Simcoe was first YCR14 and Mosaic was HBC 369. I think you’re getting the picture here… all the hops we know and love today were originally experimental hops that could have just easily been a bust.

Breeding New Hops

Experimental hops usually don’t happen organically. Some do – like Zappa out in New Mexico – but more often than not, they are carefully bred by professional hop breeders like the Hop Breeding Company (HBC), Yakima Chief Ranches and Hop Products Australia (HPA).

Hop breeders first create new cultivars by cross-pollinating different varieties of hops together, hoping that the child will exhibit the best qualities of both. This process is long and complicated, with absolutely no guarantee of success.

Hop plants are dioecious, which means that male and female reproductive organs are borne on separate plants. Only female hop plants produce cones, which are the “hops” we use in brewing beer. Male hop plants are only used in breeding programs because they do not produce cones.

After breeders have created a new cultivar from a set of parents, it is named with a numerical identifier, and the testing begins. Each new cultivar has to pass several tests before it is grown in larger test plots. Resistance against various mildews and pests are checked, alpha and oil levels are verified and potential yield amounts estimated. Some other requirements of a successful hop is that it matures at the right time for harvest, and is able to be machine-harvested. Only after the new variety passes these tests and shows promise is when a single plant is chosen from all the siblings and grown in larger quantities.

This testing process is performed thousands of times a year. Dr. Ron Beatson from NZ Hops says they “evaluate up to 5,000 offspring from different combinations of parents every year.” This amount of evaluation takes time, money and patience.

The process from pollination to test plot can take upwards of a decade or more. It took the Hop Breeding Company 13 years to grow Citra’s test plot to 21 plants. It took Nectaron 16 years to make its way into commercial production. Strata took Indie Hops only 9 years from start to finish, which they claim is very fast in the hop breeding world.

Only after a decade-plus of testing and countless brewing trials, does an experimental hop complete its transformation by receiving a trademarked marketing name. These names are necessary for the hop’s marketing push. No one talks about HBC 369… brewers only know it by the name Mosaic.

This extended timeframe for creating new hops is one of the main reasons why good hops are so damn expensive.

The Constant Threat of Failure

Even if a new hop variety passes all the tests, it doesn’t mean it becomes a success.

No one would expect to hit home runs like Citra or Simcoe every time, but the threat of “failed successes” is always there.

Satus passed all testing showed enough promise to become a trademarked variety of Yakima Chief Ranches in 1999, but has since disappeared from all suppliers and even the YCR website.

Sun is another variety that passed all the tests and was put into production by Hopsteiner, another hop breeder. Unfortunately, commercial use never took off, and this bittering hop simply faded away into oblivion.

Sometimes, a failure can be a good thing. In fact, Simcoe, Citra and Mosaic, all began their life failed as high-alpha hops. These hops were originally bred for their high-alpha content, only to be instead picked for their flavor and aromas. Those three hops have arguably started the “juicy” craze we are now seeing in craft beer.

Using New Experimental Hops

We could not find good data on how often hop cultivars fail, but it is probably safe to say it’s a high percentage. Each year, only a couple new cultivars are released by their breeders, and some of them never end up getting renamed from their original ID.

There are a handful from each breeder that we want to keep an eye on.

Hopsteiner currently has three unnamed experimental hops that are publicly available: X15619 (bittering), X13459 and X09326 (dual).

Yakima Chief Hops only advertise one experimental variety on their website: HBC 472. There are probably others, but many of the ones listed around the internet now are ones that have been recently renamed like Talus and BRU-1.

However, these breeders and others like HPA, NZ Hops, Indie, Crosby and others don’t commonly disclose when they have an experimental variety ready for commercial test brewing. They are often contracted with larger craft breweries like Sierra Nevada, Deschutes, Goose Island and Ballast Point. These breweries have the staff, know-how and facilities to provide accurate testing for the breeders. Only after the new hops pass this test, do they become available to home brewers like you and me.