Why London Ale III is the Quintessential NEIPA Yeast

I’ve tried a lot of yeasts over my time brewing. I’ve always been an IPA guy. I started out brewing west coast IPAs and stouts, but lately have been focusing primarily on New England “Hazy” IPAs.

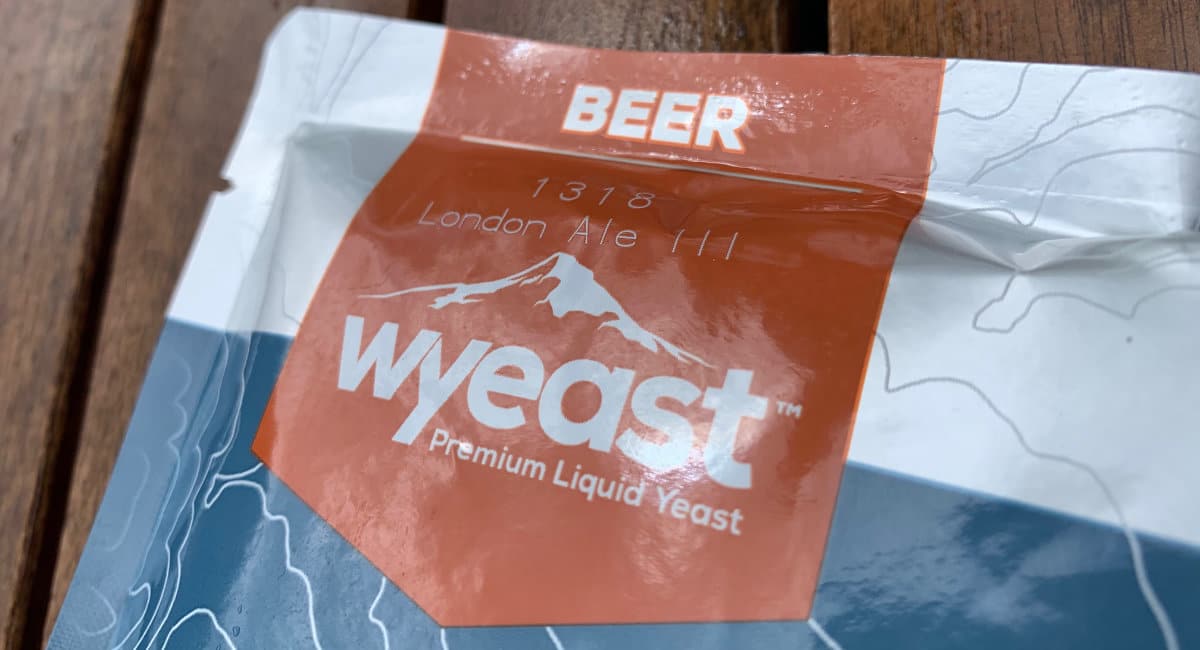

I’ve tried a lot of various yeast strains with my favorite beer style, and the only one that comes close to it is the Boddington yeast strain, or better known to brewers as London Ale III or WY1318.

While Wyeast’s specific strain is by far the most popular, there are actually plenty of other branded versions of it. The newest is Lallemand’s Verdant IPA Dry yeast, and is – at this point – the only dry version of it.

Regardless of the brand you choose, the moral of the story here is that if you are looking to make the best New England IPA possible, you need to choose this strain above all others.

Tasting Profile

London Ale III has a flavor profile that is bready, slightly tropical and leaves behind more residual sweetness than most strains. The tropical notes from this yeast goes extremely well with the flavors and aromas you typically get from IPA hops. Citrus, tropical fruit and floral all mesh with the esters this yeast produces.

My favorite part of this yeast is how it either brings the bready-ness to the table, or at least enhances the malt profile to highlight it. While this may not be a flavor everyone loves, I really enjoy a New England IPA that is a mix of fruity and bready.

Hazy

The majority of the haze created by this yeast does not drop out, even after weeks in the keg. While the haziness of a beer is not from a singular source, this yeast does a good job of keeping the haze. NEIPA haze is usually a good mix of suspended proteins from the grains, polyphenols from the dry hop and the yeast.

London Ale III yeast won’t contribute 100% of the haze in most beers, but it certainly is a great component of it.

Fuller Mouthfeel

The extra sweetness lends to the fuller mouthfeel that we all come to expect from Hazy IPAs. The attenuation of this yeast tops out in the mid 70s, which isn’t a huge jump away from the 80-ish percentage you see with other yeasts, but it makes a difference.

I’ve never had a watery beer with this yeast. This holds true even for those times I missed my starting gravity, and my BIAB efficiency was garbage.

What to Expect During Fermentation

The preferred fermentation temperature range is right in line with most ale yeasts, ranging from 64 – 74°F (18-23 °C). This yeast shows the best results if you start near the lower end of the range, then work your way up as gravity drops, usually near a max of 70-72°F.

As for the flocculation, its kind of a mystery to me. Wyeast notes their strain as a high flocculator, but this strain is very well known to be super hazy.

The attenuation is lower than most ale yeasts, leaving the resulting beer sweeter than standard yeasts.

| Optimal Temperature | 64 – 74°F (18-23 °C) |

| Flocculation | High |

| Attenuation | 71 – 75% |

| Maximum ABV | 10% |

Krausen

For those of you who aren’t initiated with this strain, expect some extremely thick krausen. I was initially concerned with how this krausen looked and felt. I had actually used this yeast many times before, but it was always in my glass carboy. Not until did I brew in my new Delta FermTank did I get up-close-and-personal with this yeast.

It had the consistency of pudding and was not oily at all. It tasted a little bitter, but I wouldn’t recommend tasting it unless you think it may be infected.

The krausen produced by this yeast will pretty much never fall to the bottom on its own. It is so thick that some brewers have had problems dry hopping on top of it since it wouldn’t let the hop pellets drop into the beer.

Harvesting & Saving Yeast

London 3 is considered a top cropping yeast. While you can still get good results taking your yeast from the bottom of the fermenter, brewers have the most luck harvesting it from the top. In fact, brewers have noted that the haze we all associate with this yeast actually begins to fade if you continually bottom crop.

The best way to do this is by sanitizing a spoon, and scooping off some of that thick krausen when it is at its highest. Place it in a sanitized mason jar, and use it within a week. If you’ve found yourself having an older batch, we would suggest building a starter.

When I have the time (and when I plan ahead), I like to overbuild my starters and reserve a little less than half for the next batch. Typically, I make a 1-2 liter starter with leftover LME and reserve about 500ml (which should work out to between 50-100 billion cells).

Speed

New, fresh pitches of London Ale III usually hit final gravity (FG) for me in about 4 days. At this point I usually hit the beer with my first dry hop, and let it sit for a few days more. Since all NEIPA beers should be kegged for stability reasons, I have no problem kegging by the 7–10 day mark knowing that if there are a few gravity points left to hit, doing so in the keg won’t cause any issues.

Related: Building a Closed Pressure Transfer Kit for my Delta FermTank

Alternative NEIPA Yeasts

I’ve actually tried a lot of different yeasts with similar recipes, and every time I’ve preferred the London Ale III batch.

Kveik such as Hornindal or Voss ferment superfast, but I’ve always found a bit of funk coming from them. They also attenuate higher, which leads to a slightly thinner mouthfeel.

Conan is probably my second favorite yeast to use with this style, but it always has less haze, a thinner mouthfeel and almost too much tropical fruit esters. While The Alchemist made the New England-style of IPA popular, their beers (while still fantastic) aren’t exactly what I am used to with my favorites.

As for exact alternatives to WY1318, you can use the following brands and get pretty much the same outcome I’ve described in this article.

- RVA Manchester Ale (RVA-132)

- Escarpment Foggy London Ale

- White Labs London Fog Ale (WLP066)

- Omega British Ale V (OYL-011)

- Imperial Juice (A38)

- GigaYeast British Haze (GY128)

- LalBrew Verdant IPA

Popular Breweries that Use London Ale III

I debated whether I should even add this section to the article. First and foremost, most breweries actually don’t disclose the yeast they use. Secondly, a lot of popular breweries have a house strain that they’ve cultivated and reused for years. This could end up being a blend of a few different strains, or one that has mutated into something completely different.

However, I will say that many clone recipes of popular New England IPAs suggest using London Ale III yeast. Most of these recipes aren’t developed by the breweries themselves, but popular opinion is that they taste very similar to the real thing.