Are All Barley Pale 2-Row Malts the Same?

When creating a recipe in a tool like Brewer’s Friend, if you type in “2-row” into the “fermentables” section, you are presented with what seems like an endless list of different products. They all have different maltsters, countries (Canadian, American, English, German…), slightly name changes (pale, 2-row, base, premium…) and a range of Lovibond ratings (1.2 – 5+).

It makes you wonder if there is any real difference between them all.

Previously we looked into the differences between Golden Promise, Pale 2-Row and Maris Otter. We found that all three of these are territory-specific 2-row pale barley malts. They are similar, but have characteristics specifically for each of their region’s “true” beer styles.

However, there is one level deeper we wanted to dig into. We wanted to know the discernible differences between the handful of common 2-row maltsters.

Are there any differences in use? Are they all produced the same way? Do they have any unique tastes?

Let’s find out.

The Setup

In order to get our list of common base 2-row maltsters, we used Brewer’s Friend recipe tool. From that, we searched their website and found each of their commonly available 2-row base malt:

- Rahr Standard 2-row (Shakopee, MN, USA)

- Breiss Pale Ale Malt (Chilton, WI, USA)

- MaltWerks Pale (Detroit Lakes, MN, USA)

- Simpsons Best Pale Ale Malt (UK)

- Thomas Fawcett Pale Ale (UK)

- Bairds Pearl Pale Ale (UK)

- Muntons Pale Planet (UK)

- Canada Malting Co (CMC) 2-row Malt (Canada)

- Gabrinus Pale Malt (Canada)

- Weyermann Pale Ale Malt (Germany)

- Bestmalz BEST Pale Ale (Germany)

I want to stress that we tried to pick the most basic product they have available. Below, we compare each of these malts on a variety of topics including color, flavors, use and customer reviews.

Color Differences

| Maltster | Lovibond (°L) |

|---|---|

| Rahr | 1.7 – 2.0 |

| Breiss | 3.5 |

| MaltWerks | 1.9 – 2.9 |

| Simpsons | 2.2 – 3.0 |

| Thomas Fawcett | 2.3 – 3.0 |

| Bairds | 2.0 – 3.0 |

| Muntons | 1.2 – 2.8 |

| Canada Malting Co. | 1.7 – 2.0 |

| Gabrinus | 1.7 – 2.5 |

| Weyermann | 2.5 – 3.3 |

| Bestmalz | 2.3 – 3.1 |

All values here were gathered from each of their respective websites and spec sheets. We used the ASBC analysis data if the maltster provided different charts. Lot analysis figures are commonly standardized based on either the American Society of Brewing Chemists (ASBC) or the European Brewing Convention (EBC), or the Institute of Brewing (IOB) standard for easy comparisons.

Also, most maltsters mention that their malts can have slight deviations from year-to-year due to the differences in growing conditions. This is the reason that grain colors are listed in ranges instead of the exact value for that particular lot or year.

One thing I learned during my research is that Pale Ale Malt is slightly more kilned than Pale Malt and will therefore have a slightly darker color. I didn’t know this distinction existed. Maltsters don’t always make it clear as to which variety they are selling, so it may be up to you to make the determination based on each of their Lovibond ratings.

- Pale Ale Malt usually is in the 2.5–3 degrees Lovibond range.

- Pale Malt is light in color and usually will be around 1.2–2.5 degrees Lovibond.

- Extra or Super Pale Malt usually has a Lovibond rating of less than 2, but there is significant overlap in colors here.

Base malts are kiln-dried with a finish heat of 180-190° F for 2-4 hours. Longer kilning times will transition barley from extra pale malt to pale malt to pale ale malt. More kilning will create darker grains.

Additionally, German malts tend to be kilned slightly more than their UK or American equivalents. This is likely due to a mix of the styles of German beers and the implementation of Reinheitsgebot, or the German Purity Law that stipulated the ingredients to be used in beer making.

It is important to also note that some UK and German maltsters will list their colors in EBC and not Lovibond. We’ve built a calculator to help you convert those numbers.

Regardless which pale malt you decide to use, a 1.5 to 2 degree Lovibond difference will not make a noticeable difference in your final beer.

Diastatic Power

Base malts are considered “base” because they are high in the enzymes that help extract the sugar from the grains. The light kilning keeps these enzymes intact, unlike the darker grains that have little to no diastatic power (DP).

| Maltster | Diastatic Power (°Lintner) |

|---|---|

| Rahr | 80 |

| Breiss | 85 |

| MaltWerks | 110-120 |

| Simpsons | 50-75 |

| Thomas Fawcett | 100 |

| Bairds | 45 (minimum) |

| Muntons | 110 |

| Canada Malting Co. | 80-82 |

| Gabrinus | 110 |

| Weyermann | 70 |

| Bestmalz | 76 |

In this chart, you can begin to see some major differences between the base grains from different maltsters. There needs to be enough DP to not only convert the starches in the base grains, but in the specialty malts in the mash as well. This means you’d usually like to see your base malt have as high a diastatic power value as possible, especially so if you are using a lot of adjuncts like chocolate grains or flaked oats.

What I also found here is that “base” doesn’t mean the same to every malting company. For example, Rahr has both a Pale Ale Malt and a 2-Row product. Their 2-row product is closer to the “extra” pale version that other manufacturers produce. The naming these maltsters use are not always congruent with others in the industry.

Protein Content

Protein levels are a big factor in brewing consistency. As a rule of thumb, it is best to use base malts that have protein levels between 9.5% and 12.5%. All the base grains we’ve selected for this comparison fall within this range.

Protein content also can be broken down into a few categories based on their solubility. However, we aren’t going to dig into these values too much because the enzymes in grains that give grains their diastatic power are in fact proteins themselves. This means that as diastatic power increases for a particular grain, so does the protein content. While this is not always a 1:1 correlation, it is a good method for quickly determining the protein content of a particular grain.

Flavor & Aroma

The largest differences with longer kilning times between extra, pale, and pale ale malts will be in their flavor profiles.

Due to having the longest kilning times, Pale Ale Malt will have a more full-bodied flavor and will provide more malty aromas than Pale Malt. Super or extra pale malts will have a greener and more sulfury aroma than normal pale malts.

In general pale malts will feature milt and subtle biscuit, bread and honey flavors. Pale base malts should have little to no roasted or nutty flavors.

Beside that generalized statement, most maltsters list a flavor profile for each of their products. Unfortunately there is not a common method for classifying these aromas and flavors, so it is very hard to normalize them all down into one chart. This is a common theme among brewing in general, as hops also have had a long history of little-to-no coordination among producers.

Malt Production

This has more to do with the malster’s process in producing the malt rather than the base malt variety itself.

Generally, there are two ways to produce malt. On the floor and in new industrialized machines. Floor malting leaves the malt slightly “under-modified”, but it gives the malt a very rich, aromatic flavor that is far more intense than is usually achieved by today’s time-efficient, industrial malting procedures.

Floor malting was the traditional way of creating malt from grain on floors made from thin tiles quarried from the Bavarian town of Solnhofen. Floor malting is more of an uneven process than the more modern mechanized solutions of today, which adds to the flavor profile. However, due to the more manual nature of floor malting, many maltsters have forgone this old method and switched over to newer methods that help increase production volumes with less manual effort.

Of all the maltsters we listed above, onlyThomas Fawcett and Weyermann either floor malt their entire product line or ave specialty products specifically that take advantage of the floor malting process.

Customer Reviews

Sifting through customer reviews of the different base malts is tricky.

Most customer reviews are anecdotal accounts of what they have experienced with a particular grain variety, maltster or seller. There are a lot of factors that are not commonly disclosed as to the exact mashing method they used, or how long the grains sat unused. What was the crush level? What were the other adjuncts used in the grist? The secondary questions like this can go on forever, so it is important to take these customer reviews with a grain of salt.

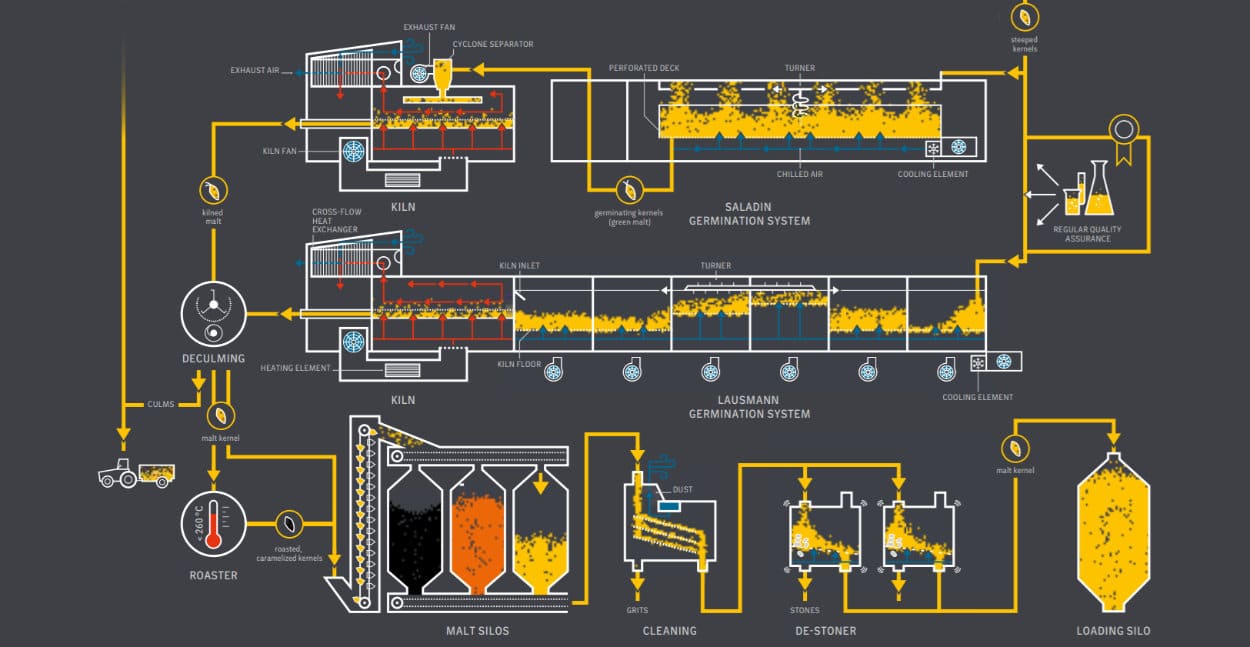

The top picture on this post was taken from the BestMalz marketing PDF.