How to Reduce Oxidation of New England Hazy IPAs

The first sign of oxidation in New England IPA is color darkening. After that, you start noticing that the hop aroma and flavors seem a bit more muted than they were originally. Finally, you start to get to the worst and most hated sign of oxidation – the “wet cardboard” off-flavor.

Oxidized beer does not taste good, and if you’ve ever had a good New England IPA turn bad, you know the exact flavor I am talking about.

New England IPAs are well known for their large dry hop charges and their cloudy, thick haze stemming from the yeast and types of grains used. Unfortunately, this same haze and hop matter that NEIPA brewers strive to achieve also cause oxygenation problems down the road as the beer ages.

While removing the haze and hops from a New England IPA would aid in preventing oxygenation, it would also defeat the style’s purpose. Because of this, mitigation is really our only option.

Let’s take a look at some mitigation steps you can take to reduce the oxygen in your finished beer.

Use Malted Oats Instead of Flaked

Oats are one of the main ingredients that create a really hazy IPA, but they can also cause major problems for homebrewers if used primarily in flaked form.

A lot of times you will find that any beer recipe that has 25% or more of oats in it will have that oat percentage broken up into a mix of malted and flaked oats. Malted oats have enzymes that flaked oats do not have, which help break down and extract the sugars from the grains. In addition, malted oats help prevent dough balls that typically form around massive amounts of flaked grains.

However, there may be another reason for using malted oats.

There are multiple studies that support the notion that swapping flaked grain for it’s malted equivalent will lead to less oxidation of the final beer. Elevated manganese levels from flaked grains are thought to increase the risk of oxidation. Many studies specifically looked at oats and the manganese levels in them appear to be the highest of any type of grain (malted or otherwise).

According to Scott Janish, author of The New IPA, “Oxygen needs to be converted to a radical activated form before it can react with other species in beer. This activation can be caused by trace metals in beer, like iron, copper, or manganese.” Scott added “Unmalted grains have more manganese than malted grains.”

“Interestingly, the grains that showed the highest manganese potential were flaked oats, which had more than three times the amount compared to a pale 2-row variety. Another malt that had slightly greater-than-average manganese content was malted wheat with 18 ppm.”

Knowing this, it may be a good idea to swap out at least half of your flaked oat grain bill percentage with it’s malted version instead. Given that malted oats still produce the same taste and haze as their flaked equivalent, this may be a no-brainer going forward for my NEIPAs.

Keg Instead of Bottle

When you bottle a beer, you need to transfer the beer into a bottling bucket, add the priming sugar, then fill each bottle full. There are a lot of steps here, all of which can add oxygen. While some homebrewers have found a way to bottle New England IPAs with success, it is still more accepted to keg these types of beers.

Most homebrewers that started out bottling and have switched to kegging will tell you that not only is it easier, but it has also helped the quality of their beer greatly.

Closed Keg Transfers (LODO)

Low Dissolved Oxygen (LODO) is an idea that focuses on moving beer from the fermentation vessel to the serving keg without the beer touching oxygen.

One of the largest influxes of oxygen into your finished beer is during packaging. While kegging your beer definitely has less opportunity to add oxygen to your beer when compared to bottling, there is still ample ways for oxygen to ruin what otherwise would have been a perfect brew.

When I first started kegging, I first purged my corny keg with CO2, then used my auto-siphon to fill the keg slowly from my glass carboy.

Outside the obvious safety factor, I decided to replace my glass carboy with a steel fermenter because it had a spigot at the bottom. This spigot allowed me to do a closed transfer into my serving keg, reducing the contact of my beer with oxygen.

To do this (mostly) closed transfer, I purchased this ball lock beer line and cut off the tap end. That cut end of the tubing then connected to the spigot of my fermenter, and the ball lock connected to the liquid post on my prepurged corny keg. I used gravity to fill the corny keg, periodically releasing the built-up pressure from the gas post.

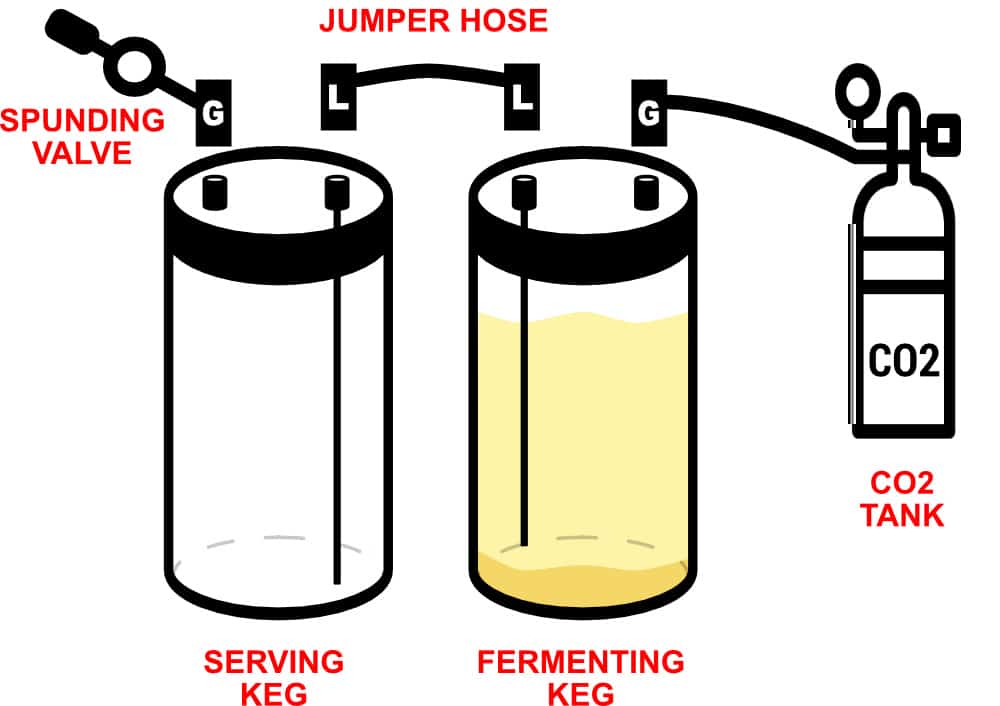

Keg Fermenting

Doing a closed keg transfer is even easier if you’ve fermented in a keg. If you’re lucky enough to have done this, you can easily transfer your beer from the fermentation keg to the serving keg with a CO2 tank and a jumper cable. Just be careful to not over carbonate it!

No Keg?

If you don’t happen to have the ability to do a closed transfer, just make sure you fill your pre-purged keg with as little splashing as possible. Splashing = Oxygen.

Use a Campden Tablet at Packaging

I use 1/2 a campden tablet crushed when I keg my New England IPAs. I got this idea from a Brulosophy test that was done that proved testers were able to tell the difference between a beer kegged with and one without sodium metabisulfite (SMB).

Campden tablets – or sodium metabisulfite (SMB) – react with dissolved oxygen in beer to remove it, thus hastening the beer from going staler faster.

It should be noted that some commenters on that Brulosophy test found that doing this causes some bad sulfury off flavors. I think the key here is to add 1/2 a tablet or 0.2-0.3g per 5 gallons or even less.

Dry Hop During Active Fermentation

A technique that has become popular among homebrewers of hazy IPA’s is to dry hop while the beer is still actively fermenting or even right at high-krausen. Dry hopping during the active fermentation phase allows the yeast to metabolise any oxygen introduced before it is able to cause negative effects on the beer.

Some homebrewing recipes will ask that you make multiple dry hops to achieve the juice-like flavors of a truly great NEIPA, but I have typically just done all dry hops in one charge. With this particular method, I have not had any problem, and it prevents me from opening the fermenter a second time – thus reducing oxygen even more.

Keep Your Beer Cold

This is something I had always done, but never really considered as a true “tip”. But it’s true… keeping your beer cold will help keep it fresher longer. There is a reason a lot of NEIPA cans have the phrase “Keep Cold, Drink Fresh” on their labels. This is an idea I first saw mentioned on Brew Dudes, who also produced a great video on this topic:

Larger Breweries Use a Centrifuge

Obviously this doesn’t work for the average homebrewer, but the centrifuge is great for the stability of the beer because it drops out all the yeast and hop matter and that stops it making it into cans. The yeast and hop matter is what creates the off flavors when they come in contact with oxygen.

Photo courtesy Simon McConico.