Why is My Homebrewed Beer Too Dark?

One of the largest complaints from those homebrewers that try to clone their favorite beer is that the color just doesn’t seem right. Here we dig into why this happens and what you can do to ensure you have the best outcome.

First, lets set the stage as to how beer color is determined. Beer color – and more specifically SRM – is calculated in laboratories using specialized equipment by passing light through a small sample of beer and recording the drop in intensity due to absorption. The calculation of the final beer you are drinking takes the SRM of each grain that went into that beer and estimates the final SRM value using the Morey calcuation.

To make matters even more confusing, most retailers online only show the Lovibond (°L) rating of grains, which is a step removed from the true SRM value.

Ok, so now that you know a bit about how beer color is calculated, lets look into some reasons why your homebrewed beer is darker (or in some cases lighter) than you expected it to be.

Based off What?

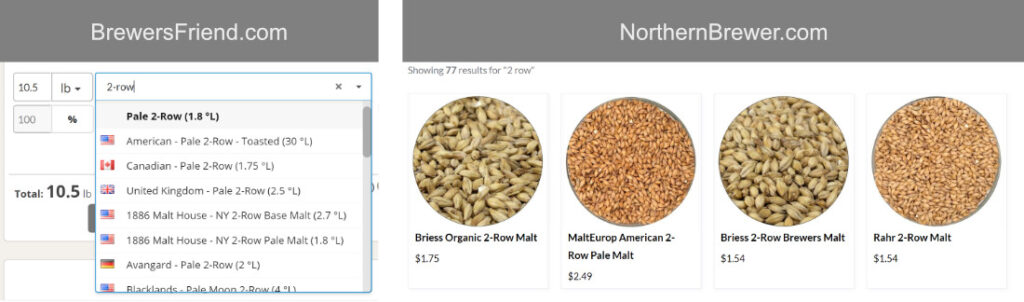

Brewer’s Friend, Beersmith and other similar beer recipe programs are notoriously bad at getting color right because they calculate color based on averages. You can see in the screenshot above that while searching for ‘2-row’ in Brewer’s Friend, you are presented with over 8 different types, all with varying degrees of Lovibond ratings.

The top four types of 2-row that came back in my NorthernBrewer search also had varying degrees of °L: 1.8, 1.6-2.4, 1.8, 1.7-2.0 respectively.

Any malts that have a range like 1.6-2.4°L, like the MaltEurop American 2-Row Pale Malt above, can throw off the color slightly if you are working off a recipe that simply uses the average 1.8°L on the default option in Brewer’s Friend.

Different Calculations

There are many calculations that are available to determine a beer’s color. They include SRM Morey, SRM Daniels, SRM Mosher, EBC Morey among a few others. While SRM Morey is the most common and universally accepted as the most accurate, they are all guesses and shouldn’t be taken as an exact science.

Compare only Finished Products

Another common problem I hear about is homebrewers worrying about the color of the wort as it goes into the fermenter. My beers always look darker going in the fermenter but the finished product comes out much lighter due to the chemical reactions from the yeast.

Different Malts from Different Maltsters

As touched on above, different malsters create their spin on a particular malt type. While a particular cereal grain may be labeled as ‘2-row pale malt’, does not mean that they are all created equally. This difference is even more pronounced as the grains are roasted longer and become even darker.

When purchasing grain from an online retailer like NorthernBrewer, you’d expect to get exactly what you place in your shopping cart. However, at your local homebrew store the exact brand or origin of the grain you are buying may be a little more opaque. This is not to suggest that the LHBS is doing anything shady, but a bucket of grain that used to be one brand may now be a different version based on what was available to the LHBS owner when it came time to repurchase.

Using Extract?

Homebrews that use extract (LME or DME) always tend to be darker than expected, and you just don’t have much control over color when using them.

Boiling the extract (particularly in a lower volume than 6 gallons) will darken it. The color change that occur when extract is boiled is called the Maillard Reaction. This reaction is similar to caramelization, and are typically responsible for the browning of your wort. While there can also be some disappointing flavor impacts to the Maillard reaction in wort, most of the time it simply causes the beer to darken significantly.

To prevent the Maillard reaction from impacting extract brews, consider adding the extract late in the boil (last 10 min) or at flame out. This will stop the significant browning of the wort from occurring.

Oxidation

Oxidation turns the beer darker, and anyone that has had a stale, oxidized beer will also tell you that it doesn’t taste very good either. Because of the flavor impact of oxidation, it is usually very easy to tell if this is the cause of your darker beer. Oxidized beer will have a wet cardboard flavor to it and it will only get worse with time (there is no reversing it).

Oxidation occurs when oxygen comes in contact with your finished beer. This usually occurs during a late dry hop, racking to a secondary fermentation vessel or during packaging.

Certain beer types are much more prone to this than others. For example, the added hop and proteins inside New England IPAs oxidize much quicker than say a stout or pilsner.

Suspension of Particles

The suspension of yeast, hop or grain particles in your beer will make it appear much darker than it would have been if those particles didn’t exist. I once had a pale ale that brightened up brilliantly after a dose of gelatin. Dropping out the sediment in your beer is the easiest and least expensive way to get the bright color you were expecting.

Gelatin, isinglass or cold crashing all have the effect of precipitating out suspended particles in your beer. The resulting clarified beer will be much lighter after one of these methods are used if sediment was the issue.

Flocculation of Yeast Types

Different strains of yeast have different flocculation rates, which in turn causes the color to be different.

Flocculation refers to the ability of yeast to aggregate together and form large flocs which then drop out of suspension. Yeast suspended in your beer can sometimes cause a “yeasty”-taste in your beer, but it can also potentially darken it (as described above in the ‘Suspension of Particles’ section).

Ideally, yeast will stay in suspension until the desired final gravity is reached and then become flocculent and drop out of the solution. However, as any experienced brewer knows, yeast do not always cooperate with this concept and may need some help to get there.

However, it should be known that all yeast strains have different levels of flocculation characteristics from low (London Ale III) to highly flocculent (London ESB). Some yeast strains like London Ale III are meant to stay suspended after finishing their job.

Generations of Yeast

The flocculence of a yeast strain will also change with serial repitching. This is due to changes in the cell wall composition and the genetic mutation as the yeast is reused many times. While this type of mutation is very strain dependent, some strains are much more stable in their flocculation rates throughout generations than others.

pH of Mash

Optimum mashing pH range is between 3.5 and 4.8. Mashing at a too high of a pH or alkalinity, will not only extract more tannins from husk material in the grain but more color too. Alkalinity and water hardness are very similar. This means that if you have hard water – or water that has high mineral content – then you may be creating a darker beer without doing anything else wrong in your brewing process.

Faulty Equipment

Faulty equipment may also be a cause of beer that is too dark. For example, hot spots on your kettle may be burning your wort. If this is your problem, you’ll be able to find scorched spots on the bottom of your pot.

Another common equipment problem is that your thermometer may need calibrated or is broken. Mashing your grains at too high of a temperature may be extracting too much color into your wort.

Length and/or Strength of Wort Boil

Longer boil times produce more concentrated wort, leading to a darker beer. It is important to make sure that if your original water volume compensates for the amount of water boil-off you expect to have. Obviously you are going to evaporate more water out of your kettle during a 90-minute boil when compared to a 60-minute one.

Boiling your wort too vigorously also can cause darkening. Boiling really hard will lead to more color development via Maillard and caramelization reactions. Having a good gentle boil is recommended and having a crazy, uncontrollable boil is never a good idea when brewing your beer.

Age of Beer

Even a non-oxidized version of beer can change color inside a can or bottle. Take a look John Kimmich of The Alchemist opening a can of Heady Topper that is 9 months old.

Different Lighting

Please don’t judge the color of your beer while it is inside a carboy. Due to the volume of liquid inside the carboy, it in no way is representative of the color of the beer when it will be served in a 16oz glass.

This also goes for comparing colors via pictures. Lighting can make a huge difference in the perceived color of a beer, so if you are comparing two samples, make sure they are together in the same lighting circumstances.

Conclusion

Ultimately if the beer tastes good, stop worrying too much about color.

The pantone colored beer bottles image at the top is courtesy http://www.txaber.net/