Understanding Everything About Dry Hopping

Dry hopping refers to any hop addition after the wort has been cooled. These additions are usually done in the primary or secondary fermenters, or directly in a keg. These hop additions are done cold-side to prevent the volatile oils from being boiled off like they would be if added to hot wort. These oils are what give your dry-hopped beer that fresh tropical, citrus, stone-fruit and pine aromas that we’ve all come to expect in heavily dry-hopped beers like New England IPAs (NEIPA).

The Science of Dry Hopping

Dry hopping does not impart much, if any, bitterness to your beers. The hops being added to the cold wort are simply being used to add aroma and flavor to beer. The hop flavor being added are very different from the flavors from the same hop variety when added to the boil or whirlpool.

Biotransformation is a little understood but powerful brewing process. Yeast will happily munch on these hops and transform them into flavors and aromas that you simply cannot get when adding them to the boil or whirlpool. This is the process that causes some of the juiciest NEIPAs you’ve ever tasted.

When dry hopping after primary fermentation has completed, the hops will release their aroma compounds into the beer, adding their distinct aromas. These aromas are usually fruity, dank, or herbal.

The Downside of Dry Hopping

Sanitization: Some homebrewers say that dry hopping runs the chance at infecting your beers since you can’t easily sanitize the hops before dropping them into your fermenter. I have never run into this problem, and think it is likely overblown by overly-cautious brewers. If you have good sanitization techniques, you will likely be fine. Plus, as the alcohol content increases in your wort, it becomes a less hospitable environment for bad bacteria to grow in any way.

Vegetal Taste: You typically want to dry hop with hop varieties that are low in cohumulone (an oil found in all hops). Some studies have suggested that dry hopping with high cohumulone hops arguably result in a more harsh bitterness or a vegetal taste in your beer. It is common to dry hop with hops that have relatively low alpha acid ratings, often around 6% or less. I have seen this first hand when trying to dry hop with a large charge of higher-than-normal cohumulone level Cashmere hops once before. You can also limit the vegetal taste added by dry hopping with 100% lupulin products like Incognito instead of the common pellet hops.

Oxidation: This is a huge problem for any heavily dry hopped beer like a hazy NEIPA. Oxygen is the kiss of death for any beer, but especially one that has been hit with a heavy dry hop charge. The wonderful oils that give you the amazing flavor and aroma are also the ones that turn dark and change to a wet-cardboard type of taste when hit with oxygen. To help combat this I usually dry hop very early in the fermentation process (i.e. high krausen) so that any oxygen I accidentally add into the wort gets processed by the still-active yeast.

Hop Creep: If you leave the hops in the wort for too long, you’ll run the risk of what is called hop creep. Hop creep is effectively the added fermentation of left over sugars due to enzymatic processes within the hop plant material. This will either increase your beer’s ABV or over carbonate the beer if left under pressure.

Which Hops Work Well With Dry Hopping?

As previously mentioned, studies have shown that you should dry hopping with low cohumulone hops to prevent adding a harsh bitterness or a vegetal taste to your beer. Also, it is common to dry hop with hops that have relatively low alpha acid ratings, often around 6% or less.

For New England IPAs, very common hops to dry hop with are Citra, Mosaic, Galaxy, El Dorado, Amarillo or Simcoe among others. Basically what you are looking for are hops classified as either Aroma or Dual purpose, which means they can be used on the cold-side of the brewhouse.

Cryo Hops in Dry Hopping

Another trend that is popular when dry hopping is the use of Cryo Hops, or lupulin powder. many popular breweries such as Other Half and The Alchemist utilize Cryo hops or lupulin powder between 30-100% of the dry hop amount. A huge benefit in using Cryo hops here is that since it is just a powder, there is much less trub loss and you are basically adding pure flavor and very little bitterness. The suggested dosing rate for Cryo hops are 1/2 the pellets amount by weight. So if a recipe wants a 4 oz Citra dry hop, you can use 2 oz of Cryo hops instead for the same amount of flavor.

Tip: Search Our Extensive Hop Database

How Much to Dry Hop

This, of course, depends on your preference and the beer styles you’re trying to emulate. However, since most dry hops are meant to impart a juicy flavor and aroma in New England-style IPAs, the typical dosing amount is between 1–2 oz (28-56 g) of hops per gallon of beer. This means up to 8-10 ounces can be used in a 5 gallon (19 l) batch. You can obviously adjust that as you prefer, so if you want just a hint of hop aroma you can go as low as a 1/2 oz (14g) per 5 gallons.

Dry hopping can use any form of hop, including fresh whole hops, loose hops, hop pellets, or concentrated hop oils. Theoretically, you can use bittering hops, but most often, only dual purpose and aroma hops are used in the dry hopping process.

How to Dry Hop

There are two common ways to dry hop: put the hops in a muslin (or similar) bag and place it into your primary or secondary fermenter, or just sprinkle the hops directly into the fermenter and let them float around freely. I have done both quite a bit, and have recently went back to just sprinkling them on top.

When using a hop bag (or muslin bag), it keeps the hop matter from clogging up your keg or racking cane, which can be a huge pain if it’s ever happened to you before. You don’t want to mess around with a keg post that is jammed up with hops. The downside to using a bag like this is twofold:

- There is decreased surface area for the hops to impart their favor in the wort. Free floating gives your hops the best chance to provide their flavor and aroma to the beer.

- Typical small-mouthed carboys are usually too small to easily get the bags in and out of. This is the reason I stopped using them. When trying to clean out my carboy after I packed my beer was a huge pain. I tried to pull them hard after just being able to grab a part of the bag from the small mouth. I also tried to cut (read: mutilate) the bag after grabbing it. Both ways worked, but they were messy and more work than was worth it.

Now, I just sprinkle the hops into the fermenter, so they can float around freely. I prevent the hop matter from clogging my racking cane, siphon or keg by doing two things:

- I cold crash the beer a day or two before I am about to bottle or keg it. Once the beer temperature drops below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, the hop matter starts to drop to the bottom of the fermenter. Sometimes I have to gently swirl the carboy to get the remaining stubborn hops to fall.

- I take the muslin bag (dipped in sanitizer of course) and wrap the end if my siphon or racking cane with it. This prevents any hop matter from getting into my keg or bottling bucket. I usually just use a rubber band that is also sanitized to hold the bag in place.

Another problem that can occur with dry hopping directly into the fermenter is that if you want to use my preferred method for reusing yeast, you are likely going to end up with spent hops being pitched into your next batch of beer. This may not be too much of a problem if your styles are pretty similar, but could be bad if you are pitching reused IPA yeast into a Kolsch or Saison.

When to Dry Hop

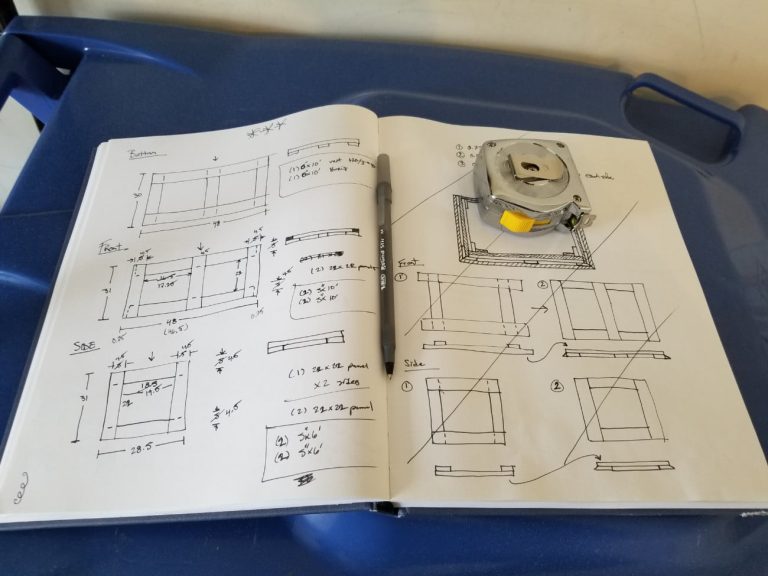

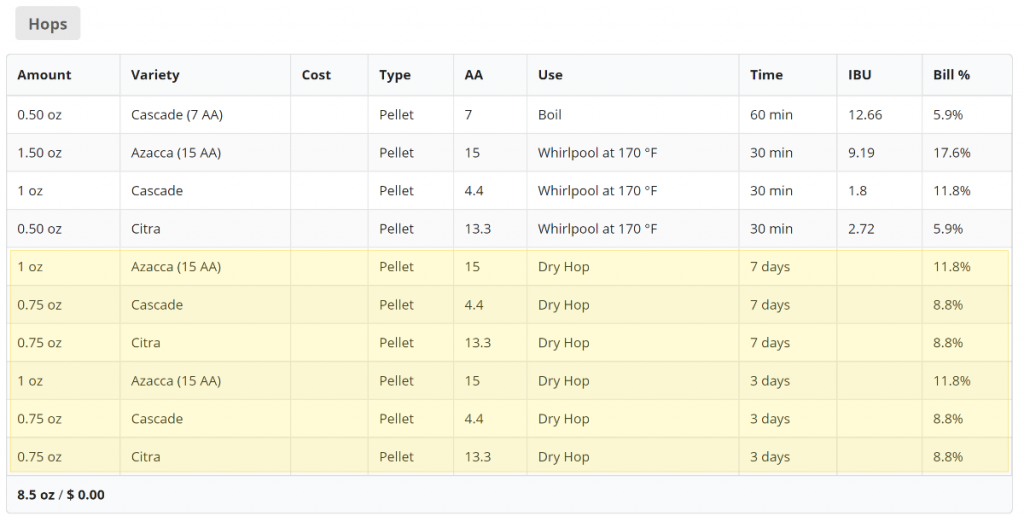

Most homebrew recipes that feature a dry hop give you a schedule that looks like the following:

The way you read this recipe, is that it is asking for two different hop charges, one with 7 days left before packaging, and the last one with 3 days left before packaging. Obviously this means that you need to kind of have an idea of when the beer will be “done”, which isn’t a time-based process as much as it is one that is done when the yeast tells you it’s done.

However, these dry hopping schedules are just recommendations and I usually adjust them a few different ways to help reduce oxidation (see above) without noticing any differences in the beer’s final taste or aroma.

I always add my first dry hop charge at high krausen. This is probably the safest time to do it because any oxygen you add while adding the charge will be instantly processed by the very active yeast.

The second dry hop charge I try to do a few days before I think the beer will be at final gravity. This is sometimes a guessing game, but after a few batches and after watching how the airlock activity is going, you’ll eventually get the hang of it. You can also keep testing the beer with a hydrometer as well to see how close it is getting to the FG.

The reason I dry hope right before FG is reached is that since there is still some expected yeast activity to occur, the hope is that they will happily much on any oxygen accidentally added to the vessel while adding my last hop charge in.

Sometimes I get lazy or nervous about oxidation and just add all the dry hops all at once in one large charge. This is probably the safest and usually with a 5 gallon batch, there isn’t much of a difference in taste or aroma in the final product. If you are staring out homebrewing, I would suggest doing one large dry hop charge at high krausen until you feel more comfortable branching out and trying different techniques.

Dry Hop Time in Beer

Studies bear out what chemical analysis has shown when it comes to hop aroma extraction. Aroma intensity was exactly the same for beers dry hopped with pellets for six hours versus when dry hopped for four days. Shorter dry hop times were also rated with higher fruity characteristics from monoterpene alcohols and thiols while longer dry hopped beers were ranked higher for herbal notes from polyphenols.

Also, in some extreme cases, heavy polyphenol extraction has been attributed to what some are calling “hop burn” in dry hopped hazy beers. If you find any of your beers are experiencing “hop burn”, consider reducing the amount of time the dry hops are suspended in the beer.